To return, or not to return to the office? In the post-Covid world, less contentious compromises will be key to attracting and retaining top talent.

The increasingly vociferous debate over whether employees should be made to return to the office comes as no surprise. After all, with some managers remaining unused to having little physical visibility of their teams, and with employees, on the other hand, enjoying their liberation from painful commutes and growing more comfortable with working remotely, conflict seems inevitable.

In recent weeks, we’ve seen large companies make the news because of these battles. Apple CEO, Tim Cook told its global workforce of over 100,000 employees that they’d have to return to the office for three days a week by early September.

“Video conference calling has narrowed the distance between us, to be sure, but there are things it simply cannot replicate. I look forward to seeing your faces. I know I’m not alone in missing the hum of activity, the energy, creativity and collaboration of our in-person meetings and the sense of community we’ve all built,” he said.

But not everyone agreed. In an open letter to Cook, some employees voiced their unhappiness while pointing out that they managed to deliver “the same quality of products and services that Apple is known for, all while working almost completely remotely.”

More recently, Morgan Stanley chief, James Gorman said it’s time for the bank’s New York workers to head back to the office now that more people are getting vaccinated for Covid-19 and life is slowly returning to normal.

JPMorgan CEO, Jamie Dimon is also clearly not sold on operating in the virtual environment.

“Most professionals learn their job through an apprenticeship model which is almost impossible to replicate in the Zoom world,” he said.

“Over time, this drawback could dramatically undermine the character and culture [of the company.],” he added.

Various companies have expressed concerns about remote work including how it curtails collaboration, and limits spontaneous learning and innovation.

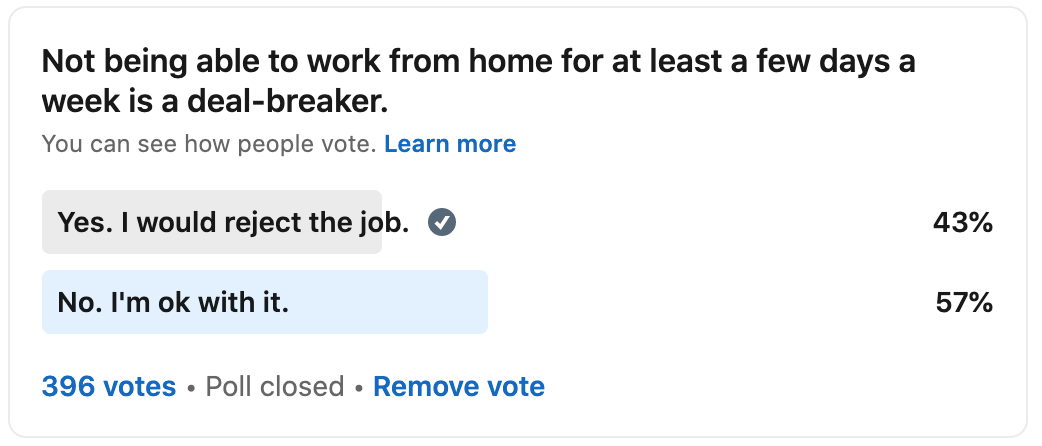

In the meantime, numerous surveys show that many employees whose job roles enable them to work from home, don’t want things to change. Our own LinkedIn polls back this up. In fact, if a new job doesn’t allow working from home at least a few days a week, a sizeable number of respondents said they would reject it.

Results of PeopleSearch’s recent LinkedIn poll.

Considering conflicting views on the matter, perhaps the best way for companies to manage the situation without fear of losing top talent or not being able to attract any in the foreseeable future is to actively listen to both leaders and subordinates, and make a case for compromise on each side.

If you’re in a position to influence how this battle unfolds, here’s how you can begin encouraging less contentious compromises:

1. Find out what leaders’ real concerns are and address them with data-driven insights and solutions

Identifying leaders’ reasons for opposing remote work is important if you want to truly address the problems. It could just be that one or two members of their teams did not pass the productivity test while working from home.

Whatever the case, in order to achieve a compromise, you would have to draw attention to team-specific data as well as company-wide data.

For instance, while one or two members of the team skived, how did the others do? Overall, was the team in fact more productive and collaborative? Are there tools that leaders can use to increase productivity and collaboration?

On a larger scale, perhaps the option of remote work has allowed the company to more easily recruit top talent, even talent across borders and this has had a positive impact on the bottom line. Once they see this, leaders who care about the bottom line are likely to rethink their insistence on a return to the office.

It could very well be that leaders aren’t comfortable managing remote workers because they just don’t know how to. Leadership development might be in order in such cases. For instance, leaders who like spontaneous check-ins with their team members might need to be shown how these can be replicated virtually through downloadable apps. Others might need communication coaching to get the most out of virtual brainstorming sessions.

2. Find out what employees’ concerns are and address these as well

Employees who prefer to work remotely all week could have legitimate concerns such as long commutes, the inefficiencies of working on site or childcare obligations. Companies need to address these head-on as well.

For instance, if management is concerned about collaboration and innovation, instead of requiring employees to come into the office a certain number of days a week, can in-person appearances be restricted to special meetings such as departmental brainstorming sessions? This would address employees’ concerns about daily commutes.

Others may not be convinced that in-person sessions are more productive than virtual ones. Do you have data to persuade them otherwise?

Can working on site be made more efficient so that employees don’t have to spend an entire day at the office? Perhaps call fewer meetings which many employees consider a waste of time.

Those who are concerned about childcare would also certainly appreciate such services being made available within the building if they are required to work on site. Companies may want to consider providing these.

Are there any other benefits that you can offer to those who are reluctant to work on site? Perhaps shorter working hours to compensate for the time they spend commuting.

3. Constantly review and recalibrate to ensure talent acquisition and retention

Once each side is presented with data-driven insights into the opposing stance, a less contentious compromise becomes more likely.

However, companies should consider how their competitors are dealing with this issue and whether they’re able to attract more and better talent as a result of greater flexibility.

Also, continually seeking feedback from your existing and potential employees is vital. As new generations of people enter the workforce, their expectations of flexibility should inform your talent acquisition and retention strategies.

Leave A Reply